We saw it with the Internet in the late 90s and iTV in the early noughties, now mobile TV is the disruptive technology du jour.

We saw it with the Internet in the late 90s and iTV in the early noughties, now mobile TV is the disruptive technology du jour.

All this year’s major TV industry gatherings – MipTV in Cannes, August’s Edinburgh International TV Festival and the RTS in Cambridge – have showcased mobile.

And in recent weeks, Sky, ITV and Channel 4 have all announced plans for mobile video content.

It’s easy to be swept up in the hype, and persuasive arguments abound.

It’s easy to be swept up in the hype, and persuasive arguments abound.

At last week’s inaugural mobile TV Forum, the atmosphere was upbeat. BT, Arquiva, Fremantlemedia and Universal all gave impassioned presentations suggesting mobile TV is just around the corner.

BT’s Emma Lloyd (left) said the mobile video “Livetime” service would be UK-wide on Digital One’s DAB network by June 2006.

Claire Tavernier from Fremantlemedia (right), owner of Neighbours and Baywatch, said “Fremantle TV” would launch on US mobile networks before the end of the year.

Claire Tavernier from Fremantlemedia (right), owner of Neighbours and Baywatch, said “Fremantle TV” would launch on US mobile networks before the end of the year.

And Cedric Ponsot from Universal (below left) reported on “Label Studio TV” – a mix of ten different mobile music channels – which launched on France’s SFR 3G network in July.

“We’re combining two of the most consumer products of all time” said Arqiva’s Hyacinth Nwana (below right) in his keynote – the underlying subtext was: how can we go wrong?

But is the industry is in danger of death by over-sell before it’s even arrived?

But is the industry is in danger of death by over-sell before it’s even arrived?

Forecasters are predicting untold riches. A recent report from Informa estimates the global mobile entertainment market to be worth £24bn by 2010. Venture capitalists are already expressing an interest in mobile TV projects. (At the forum, Justin Judd of i-rights was one such example, saying he had “unlimited funds” available for the right idea.)

This is all sounding very familiar – we’ve been here before. As with the early days of the Internet and iTV, business models are unclear. Hurdles include lack of appropriate content – including rights clearance on existing properties, lack of spectrum and unproven consumer demand.

This is all sounding very familiar – we’ve been here before. As with the early days of the Internet and iTV, business models are unclear. Hurdles include lack of appropriate content – including rights clearance on existing properties, lack of spectrum and unproven consumer demand.

At the forum, BT’s Lloyd revealed she’d had to fully-fund the content channel, Blaze TV, to complete the offng for current trials. “We need to kickstart content development” she admitted.

While advertisers were mooted as one possible source of funding, Fremantlemedia’s Tavernier thought they were “scared to invest” in mobile TV, “because of lack of consumer research and lack of structures in place”.

Tavernier also talked about rights, revealing that although Fremantlemedia owned worldwide TV rights to Mr Bean and The Benny Hill Show, both Rowan Atkinson and Benny Hill’s widow had said no to mobile distribution.

Tavernier also talked about rights, revealing that although Fremantlemedia owned worldwide TV rights to Mr Bean and The Benny Hill Show, both Rowan Atkinson and Benny Hill’s widow had said no to mobile distribution.

Eirik Solheim from NRK (left), the Finnish public service broadcaster, admitted that every so often their mobile TV broadcasts had cut to video of fish swimming in a tank – as not all programme rights had been cleared.

The most telling figures came in the final session of the conference: “Viewers don’t see their mobile as an entertainment device” said Enpocket’s Jeremy Wright (right). “They see it first and foremost as a communicator.”

The most telling figures came in the final session of the conference: “Viewers don’t see their mobile as an entertainment device” said Enpocket’s Jeremy Wright (right). “They see it first and foremost as a communicator.”

Wright pointed to figures from a recent Enpocket survey showing that sharing photos of family and friends was the number one multimedia option; videocalls with family and friends were number two. Mobile TV came bottom.

As traditional broadcast models deteriorate, and the rise of the semantic web places social software at the centre of everything, the service I would back would be completely user-generated.

But the smart money will be watching from the sidelines.

Hyundai Telematic Korea have announced their way-posh Roadbank HTMS 18800 DMB navigator, an ultra slim, in-car navigation system with a hefty 7 inch touch screen.

Hyundai Telematic Korea have announced their way-posh Roadbank HTMS 18800 DMB navigator, an ultra slim, in-car navigation system with a hefty 7 inch touch screen. As well as offering navigation tools, the Roadbank comes stuffed with multimedia widgets, doubling up as a high end media console with support for movie playback formats like WMV9, MPEG-1/2/4, DivX, Xvi and H.264. It can also display digital photos too.

As well as offering navigation tools, the Roadbank comes stuffed with multimedia widgets, doubling up as a high end media console with support for movie playback formats like WMV9, MPEG-1/2/4, DivX, Xvi and H.264. It can also display digital photos too. The Roadbank HTMS 18800 DMB runs on Windows CE 5.0 and comes with 64 MB of Nand Flash with a SD card slot providing memory expansion options.

The Roadbank HTMS 18800 DMB runs on Windows CE 5.0 and comes with 64 MB of Nand Flash with a SD card slot providing memory expansion options. Yet more proof that Koreans are spoilt rotten when it comes to having the very latest must-have mobile gadgets comes in the form of Samsung’s brand new phone – displayed, as ever, by scantily clad models.

Yet more proof that Koreans are spoilt rotten when it comes to having the very latest must-have mobile gadgets comes in the form of Samsung’s brand new phone – displayed, as ever, by scantily clad models. The chunky black clamshell phone also lets users switch between having a small Picture in Picture (PiP) display showing the secondary channel or splitting the display in half, with the two selected channels sharing the total viewing area.

The chunky black clamshell phone also lets users switch between having a small Picture in Picture (PiP) display showing the secondary channel or splitting the display in half, with the two selected channels sharing the total viewing area. Naturally, users can also elect to fill the screen with just the one channel for fuddy-duddy, old-school types who are satisfied with just one channel playing simultaneously.

Naturally, users can also elect to fill the screen with just the one channel for fuddy-duddy, old-school types who are satisfied with just one channel playing simultaneously. No relation to the fabulous football team known as the Bluebirds, the Korean electronics company Blue Bird have announced their shiny new BM-300 T-DMB Personal Digital Assistant (PDA).

No relation to the fabulous football team known as the Bluebirds, the Korean electronics company Blue Bird have announced their shiny new BM-300 T-DMB Personal Digital Assistant (PDA). Although the 2.8 inch touchscreen TFT-LCD (QVGA) display looks like a bit of a whopper, it can only support a miserly 240 x 320 pixel resolution -a bit of a disappointment for a PDA and hardly likely to enhance the TV watching experience,

Although the 2.8 inch touchscreen TFT-LCD (QVGA) display looks like a bit of a whopper, it can only support a miserly 240 x 320 pixel resolution -a bit of a disappointment for a PDA and hardly likely to enhance the TV watching experience, Memory can be further expanded via an SD SDIO card slot.

Memory can be further expanded via an SD SDIO card slot. More flexible than a Russian athlete in a vat of oil, Samsung’s double-flipping DMB phone offers a novel twist on the clamshell format.

More flexible than a Russian athlete in a vat of oil, Samsung’s double-flipping DMB phone offers a novel twist on the clamshell format. As well as the DMB functionality, the Samsung SPH-B1300 serves up the usual advanced mobile feature set, complete with a two megapixel digital camera and built-in MP3 player.

As well as the DMB functionality, the Samsung SPH-B1300 serves up the usual advanced mobile feature set, complete with a two megapixel digital camera and built-in MP3 player. We can expect more details about the Samsung SPH-B1300 to be revealed at the CeBit 2006 show in Hannover next month.

We can expect more details about the Samsung SPH-B1300 to be revealed at the CeBit 2006 show in Hannover next month. Two recent studies into mobile TV on 3G mobile phones have managed to produce rather inconclusive results concerning the willingness of the great British public to use the service and how much they’d be prepared to pay for it.

Two recent studies into mobile TV on 3G mobile phones have managed to produce rather inconclusive results concerning the willingness of the great British public to use the service and how much they’d be prepared to pay for it. The feedback seemed back-slappingly reassuring, with 83 per cent of the triallists “satisfied” with the service, and 76 per cent indicating they’d be keen to take up the service within 12 months.

The feedback seemed back-slappingly reassuring, with 83 per cent of the triallists “satisfied” with the service, and 76 per cent indicating they’d be keen to take up the service within 12 months. “This trial is further illustration that we are moving from a verbal only to a verbal and visual world in mobile communications,” said David Williams, O2’s technology chief.

“This trial is further illustration that we are moving from a verbal only to a verbal and visual world in mobile communications,” said David Williams, O2’s technology chief. In a feast of digital convergence, Pantech & Curitel have announced the launch of their new multimedia-tastic PT-S160 phone.

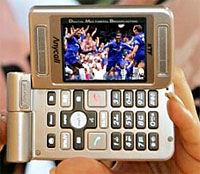

In a feast of digital convergence, Pantech & Curitel have announced the launch of their new multimedia-tastic PT-S160 phone. The PT-S160 doubles up as a PMP (Portable Multimedia Player) and a satellite DMB receiver, with a sliding design only showing keys for DMB functions when closed.

The PT-S160 doubles up as a PMP (Portable Multimedia Player) and a satellite DMB receiver, with a sliding design only showing keys for DMB functions when closed. The screen can be switched between landscape and portrait formats.

The screen can be switched between landscape and portrait formats. The makers claim a talk time of 300 minutes and a hefty standby time of 300 hours (although we’ve no idea how long you’ll get when watching TV).

The makers claim a talk time of 300 minutes and a hefty standby time of 300 hours (although we’ve no idea how long you’ll get when watching TV). We saw it with the Internet in the late 90s and iTV in the early noughties, now mobile TV is the disruptive technology du jour.

We saw it with the Internet in the late 90s and iTV in the early noughties, now mobile TV is the disruptive technology du jour. It’s easy to be swept up in the hype, and persuasive arguments abound.

It’s easy to be swept up in the hype, and persuasive arguments abound. Claire Tavernier from Fremantlemedia (right), owner of Neighbours and Baywatch, said “Fremantle TV” would launch on US mobile networks before the end of the year.

Claire Tavernier from Fremantlemedia (right), owner of Neighbours and Baywatch, said “Fremantle TV” would launch on US mobile networks before the end of the year. But is the industry is in danger of death by over-sell before it’s even arrived?

But is the industry is in danger of death by over-sell before it’s even arrived? This is all sounding very familiar – we’ve been here before. As with the early days of the Internet and iTV, business models are unclear. Hurdles include lack of appropriate content – including rights clearance on existing properties, lack of spectrum and unproven consumer demand.

This is all sounding very familiar – we’ve been here before. As with the early days of the Internet and iTV, business models are unclear. Hurdles include lack of appropriate content – including rights clearance on existing properties, lack of spectrum and unproven consumer demand. Tavernier also talked about rights, revealing that although Fremantlemedia owned worldwide TV rights to Mr Bean and The Benny Hill Show, both Rowan Atkinson and Benny Hill’s widow had said no to mobile distribution.

Tavernier also talked about rights, revealing that although Fremantlemedia owned worldwide TV rights to Mr Bean and The Benny Hill Show, both Rowan Atkinson and Benny Hill’s widow had said no to mobile distribution. The most telling figures came in the final session of the conference: “Viewers don’t see their mobile as an entertainment device” said Enpocket’s Jeremy Wright (right). “They see it first and foremost as a communicator.”

The most telling figures came in the final session of the conference: “Viewers don’t see their mobile as an entertainment device” said Enpocket’s Jeremy Wright (right). “They see it first and foremost as a communicator.”