As more people take up digital television, whether through Freeview, Sky or other means, the enhanced viewing experience becomes the norm rather than the exception. For instance enhanced sport broadcasts, such as BBC coverage of both Wimbledon and the Olympics, offer viewers the opportunity to tailor the broadcast programming to their interests by enabling them to watch events that would not otherwise be available. Likewise Sky’s fenhanced football allows viewers to choose the commentators and camera angles. News multi-screen offers similar flexibility in navigating news content. Yet interactive drama programmes are often regarded as the holy grail of enhanced television. The scripted linear narrative is seen as a barrier to interactivity. So when producers of the Five soap Family Affairs announced that they planned to broadcast an interactive episode in May 2004, pundits were intrigued. Theirs was the Big Brother version of interactivity – viewers were asked to vote, by phone, on the outcome of a love triangle. The phone vote generated extra income for the broadcaster and new viewers for the programme. On the record, the producers were delighted to offer a television first. However, when asked about the interactive episode off the record, a very senior executive involved at all stages of development and production said at the time, “Never again”. It turns out that accommodating even such a limited element of uncertainty in the narrative posed great difficulty for future storylining and production schedules.

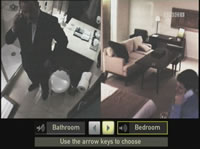

More recently the BBC has claimed to offer yet another enhanced drama first with interactive Spooks. The third series of this successful spy drama began transmission on BBC1 Monday 11 October. Unlike Family Affairs’ tentative foray into interactivity, viewers will not be voting on Spooks storylines. (If they could, they’d most certainly vote to keep Tom Quinn, the main character played by Matthew Macfadyen who exits the show in Episode 3.) Instead immediately after the programme, digital viewers are invited to find out if they have what it takes to make it as a spy. Led by Harry Pearce (a crossover character from the television series portrayed by Peter Firth), participants take a series of scored tests that examine essential espionage skills such as memory, reaction and observation. From Episode 6 viewers will be able to participate in a mission that was written by Steve Bailie, an experienced writer of television drama. “The aim,” Sophie Walpole BBC’s Head of Interactive Drama & Entertainment told us, “is to offer fans a deeper relationship with both the programme and its characters.” In addition, Walpole pointed out, “fans will get something back – they’ll get to know a little about themselves.”

More recently the BBC has claimed to offer yet another enhanced drama first with interactive Spooks. The third series of this successful spy drama began transmission on BBC1 Monday 11 October. Unlike Family Affairs’ tentative foray into interactivity, viewers will not be voting on Spooks storylines. (If they could, they’d most certainly vote to keep Tom Quinn, the main character played by Matthew Macfadyen who exits the show in Episode 3.) Instead immediately after the programme, digital viewers are invited to find out if they have what it takes to make it as a spy. Led by Harry Pearce (a crossover character from the television series portrayed by Peter Firth), participants take a series of scored tests that examine essential espionage skills such as memory, reaction and observation. From Episode 6 viewers will be able to participate in a mission that was written by Steve Bailie, an experienced writer of television drama. “The aim,” Sophie Walpole BBC’s Head of Interactive Drama & Entertainment told us, “is to offer fans a deeper relationship with both the programme and its characters.” In addition, Walpole pointed out, “fans will get something back – they’ll get to know a little about themselves.”

According to the BBC, the number of unique users for the Spooks Website during the second series “ran into the hundreds of thousands.” The decision to develop and produce the interactive platform was taken because the producers had such a strong proposal. According to Walpole, “ The BBC is always looking at ways to develop its content. But Spooks was not singled out for development in this way. The producers had a really good proposition.” She continued, “ The inspiration and vision of Andrew Whitehouse (the producer of Spooks’ interactive content) was incredible. We had a great producer with a great idea.” The enhanced TV elements are intended to complement the revamped Website so that, although the site also offers a spy training academy, the experiences are completely different. “The Spooks superfan who goes to both the Website and the interactive elements will not feel like they’ve had a similar experience,” said Walpole. Figures for new users of the Website or users of the enhanced television platform after transmission of the first episode are not yet available.

When asked how technology affected the development of enhanced television in general, Walpole stated that while it is technically possible, the BBC opted not to transmit enhanced Spooks via broadband because they wanted it to be seen by as many viewers as possible. “Although they continue to grow, broadband audiences are still small.” Looking to the future Walpole said she was certain that the BBC would make this type of rich content available to broadband users, possibly as soon as next year.

From what I’ve seen so far, the BBC has reason to be proud of interactive Spooks. By recognising that interactive drama doesn’t necessarily infer gimmicky phone votes (aka viewer extortion) or ceding control of the narrative to the audience, they deftly avoided the traps that frustrated at least one Family Affairs executive. The production values on Spooks are really very high indeed. And the spy training modules transmitted after Episode 1 were good fun. Most importantly, they lend themselves quite nicely to a shared experience – an element of the interactive experience that is essential for television audiences. The aim of providing a way for fans to develop a closer relationship with the programme is definitely achieved. If the enhanced Spooks disappoints at all, it is that the enhancements are extremely limited. The spy training takes approximately 30 minutes to complete – that’s a bit too long. Unfortunately, there’s no way to navigate through the game; participants must start at the beginning and move through to the end to get scores. Also, the training modules will be repeated after Episodes 2 through 5 and the narrative mission transmitted after Episode 6 will be repeated after Episodes 7 through 10. While this offers viewers the opportunity to practice their skills it means that, in effect, there are only 2 unique enhancements throughout the 10-week run. That’s a great shame because they’ve done such a good job of creating enhanced Spooks that I really would have liked more!

In the UK, Episodes 3 – 10 of Spooks will be broadcast Mondays at 21.00 on BBC1. Episodes are repeated on Saturdays at 21.10 on BBC3 followed by an advance transmission of the next episode at 22.10. The interactive elements are broadcast immediately after transmission on both channels.

After all the hype, the BBC’s virtually-virtual gameshow Fightbox [

After all the hype, the BBC’s virtually-virtual gameshow Fightbox [ over-the-shoulder shots (right) of the contestants which showed them in their pod displaying their computer monitor action in the foreground, in the middle-ground the virtual arena action and finally the real arena and audience action in the background. In another, there was a low shot from the arena floor looking up through one of the virtual challenges, the helix. Both these shots, amongst others, helped to create depth of vision, contributing a sense of scale and density to the action. At no point did the huge arena appear to be empty even though, in the “Real World” it was. (In reality, the studio audience watched the gaming on a massive screen.) I ought to mention the graphics too. Although gamers’ expectations are always increasing, visually the graphics in Fightbox are fairly good. There was a consistency between the studio lighting and the graphics which was so good that virtual shadows were created which matched the real ones. Now that’s attention to detail!

over-the-shoulder shots (right) of the contestants which showed them in their pod displaying their computer monitor action in the foreground, in the middle-ground the virtual arena action and finally the real arena and audience action in the background. In another, there was a low shot from the arena floor looking up through one of the virtual challenges, the helix. Both these shots, amongst others, helped to create depth of vision, contributing a sense of scale and density to the action. At no point did the huge arena appear to be empty even though, in the “Real World” it was. (In reality, the studio audience watched the gaming on a massive screen.) I ought to mention the graphics too. Although gamers’ expectations are always increasing, visually the graphics in Fightbox are fairly good. There was a consistency between the studio lighting and the graphics which was so good that virtual shadows were created which matched the real ones. Now that’s attention to detail!